Around 60 different operas are staged at the world-famous Vienna State Opera each year. Tonight, however, the awe-inspiring 19th-century neo-romantic structure is not reverberating to the sound of Mozart’s Don Giovanni or Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, but rather the gruff idle of two Bugatti EB110Ss, the illustrious French marque’s final factory-built racing cars.

The world-famous opera house, which is commonly considered the spiritual centre of the City of Music, is the traditional starting point for the 24 Minutes of Vienna. The secretive race was born in the 1920s by aristocratic playboys who’d tear around the affluent Ringstrasse with their Bugatti Type 35s under the cover of darkness, before joining revellers of Vienna’s famous all-night balls at Café Schwarzenberg for early-morning goulash and beer.

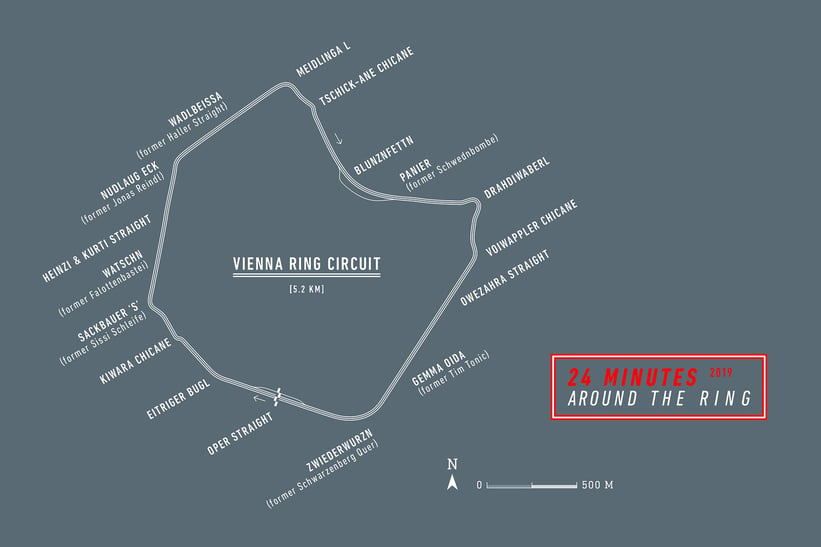

Ever since then, Bugatti evangelists have descended on the historic five-kilometre ‘Lord of the Ring Roads’ every few years to romanticise about the past and follow in the tyre tracks of those early disciples of the marque – usually to the dismay of the Austrian authorities and parliament, the latter of which happens to be prominently located on the Ringstrasse.

Said parliament also happens to have been recently rocked by the ‘Ibiza-gate’ scandal (if you’re not familiar, it’s definitely worth Googling) and in its current state of disarray ahead of a snap election in September, it hopefully has greater priorities than worrying about an under-the-radar motor race on its doorstep. The stage is thus set for another 24 Minutes of Vienna.

Unless you’ve been living in hiding, you’ll know that Bugatti is celebrating its 110th anniversary this year. And if the widespread rumours are to be believed, the marque will reveal a modern-day homage to the EB110 Supersport at Pebble Beach in August. It therefore seemed entirely appropriate to bring arguably the two most significant examples of Romano Artioli’s 1990s supercar built, the 1994 Bugatti EB110S Le Mans (LM) and 1995 Bugatti EB110S Sport Competizione (SC), to Vienna.

Before we wave the figurative chequered flag and unleash some 1,300 horses loose on the Champs-Élysées of Vienna, it’s time for a short history lesson over traditional wiener schnitzel – and yes, that is an EB110’s turbocharger, BBS rim and fuse box cover masquerading as centrepieces.

As if Bugatti’s Italian chapter could have gotten any more audacious back in the 1990s, the decision was made to take the EB110 endurance racing. Bugatti was a company built on motorsport success, after all, and Artioli believed that in addition to validating ‘his’ Bugatti, the experience would result in enhanced brand image and further technological innovation.

The trouble was that, like the McLaren F1, the EB110 was designed from scratch as a refined supercar for the road and therefore fundamentally flawed as a racing car. But that certainly wasn’t going to stop Bugatti’s determined and insatiably enthusiastic engineers in Campogalliano from giving the transformation a go.

Funds and expertise were sought from key partners, the most prominent of which was the Synergie racing team in France, and in a scarcely believable three months, the blue EB110S LM was born in Bugatti’s Reparto Esperienze skunkworks, ready to compete at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1994. In the most traditional sense, the car was driven to Le Mans on the public roads accompanied by the EB110 GT factory demonstrator and a police escort. Artioli never did anything by halves.

At the race Ettore Bugatti won outright exactly 55 years before and forged such a reputation among the fiercely patriotic French public, the EB110S LM – which retained the core DNA of the road-going Supersport, albeit in a much more technologically advanced package – in the hands of Alain Cudini, Eric Helary and Jean Christophe Boullion held strong and firm, despite a number of turbocharger-related technical gripes. That was until the 23rd hour, however, when an accident on the Mulsanne Straight forced a desperately late retirement.

The result mattered little. For the guys in Campogalliano, the car’s encouraging performance was a victory in itself and led to the creation of a second, more hardcore and further developed racer, the SC, for use in the popular IMSA series across the pond. And again, the car showed promising performance.

Alas, Bugatti Automobili folded amid a global recession and, as Artioli claims, industrial sabotage, and the motorsport world was left to wonder what might have been from these turbocharged titans. For a more comprehensive snapshot of Bugatti’s balls-out racing endeavours in the 1990s, this beautifully shot documentary is well worth a watch.

Back to Vienna. The very first major building erected on the Ringstrasse following the road’s construction in the 19th Century, the Vienna State Opera feels like the perfect starting point for an altogether more fitting reason.

When Volkswagen’s Ferdinand Piëch superseded Romano Artioli as the third patriarch of Bugatti in 1998, his brief for what would become the Veyron was clear: it was to be extremely fast, extremely powerful and elegant and refined enough so as not to embarrass him and his wife as they arrived at the opera. Now that Volkswagen’s Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S. has officially recognised Artioli’s Bugatti Automobili S.p.A., it feels quite cheeky seeing these hilariously impractical Campogalliano-built racers – warts, warpaint and all – parked outside Piëch’s local opera house. Why else do you think our drivers donned their tuxedos?

With midnight long passed and an abrupt downpour having cleared the Ringstrasse of the young revellers enjoying their end-of-term celebrations at the myriad outdoor bars, it’s time to go. It takes very something special to divert your attention away from Vienna’s spectacular architecture, a curious mix of the Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque and classical styles. But the sight and sound of two braying EB110S racers weaving through traffic and spurting flames on the Oper Straight, past the Volksgarten or into the Drahdiwaberl curve manage it with ease.

It’s at this point that, rather regrettably, we must inform you that the so-called 24 Minutes of Vienna is actually the work of fiction – a fun idea we concocted to romanticise what was a truly unforgettable evening in Vienna with these fabulous Bugatti racers. But in a world where fake news is rife and rumours concerning Bugatti’s Pebble Beach reveal have reached boiling point, it felt just right.

It also felt right to shed further light on the EB110, a car which has been undeservedly forgotten for far too long, but whose future looks bold and bright thanks to Bugatti’s long-overdue recognition of Artioli and his daring dream. These factory-built racers, in particular, represent the Campogalliano era best – they’re true technological tours de force that honour Ettore’s legacy and epitomise the ‘what could have been’ mystique and romance of Bugatti Automobili. Something tells us you’ll be seeing a lot more of them in the very near future. Thank you, Vienna!

Photos: Rémi Dargegen for Classic Driver © 2019