What are your earliest automotive memories?

I went to watch the 24 Hours of Le Mans every year with my dad, as he worked for the company who oversaw the transmission of the race on television. Standing in the middle of all the cars on the grid or, later at night, watching them blast by on the Hunaudières, definitely got me hooked for life.

Could you tell us about your background in art?

I express myself with sketches — it’s my way of communicating. From an early age, I took part in competitions, resulting in several prizes and collective exhibitions. I’ve always had a deep desire to be an artist because of the creative freedom it gives me. But I decided to study industrial design so that I could get a job and continue to do art on the side, not bound by financial or commercial requirements. On the other hand, the interesting things about design are the restrictions, compromises, and challenges — you never really have a blank canvas.

Which artists are you most inspired by?

My favourite artists are Robert Delaunay, with his incredible feeling of speed, use of colours, and dynamic and rhythmic forms; Pierre Alechinsky, with his free-hand calligraphy paintings and collages on canvas; Bernar Venet, with his mathematic approach to art and simplicity of line; Hans Hartung, with his incredible gestural abstract style; and finally, Pierre Soulages, with his graphical and textural approach.

How would you describe the art you’re currently producing?

I can’t deny that I love speed — not always for its own sake but for being in control of it. There’s a huge responsibility that comes with speed, and it requires concentration and respect. My latest works embody the fact that, when exercised with care and precision, driving is hugely rewarding.

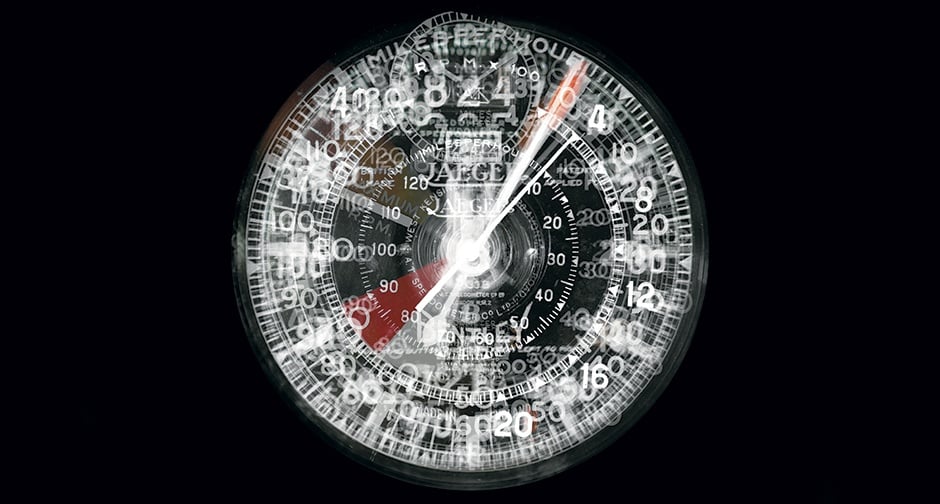

For my two-dimensional art, I studied chronophotography, an antique photographic technique from the Victorian era that captures movement in several frames of print. These prints can be arranged either like animation cells or layered in a single frame. It’s a predecessor to cinematography and moving film. My ‘Chronospeedometers’ series comprises 200x200cm prints of 35 selected iconic speedometers, all compressed into one single image that can be looked at in one moment. Visually, it draws you in and gets you to try and figure out how these visual traces relate to the source material. I like the way the source material is my own photography and that I can create visually interesting yet semi-abstract imagery by means of a clearly defined process.

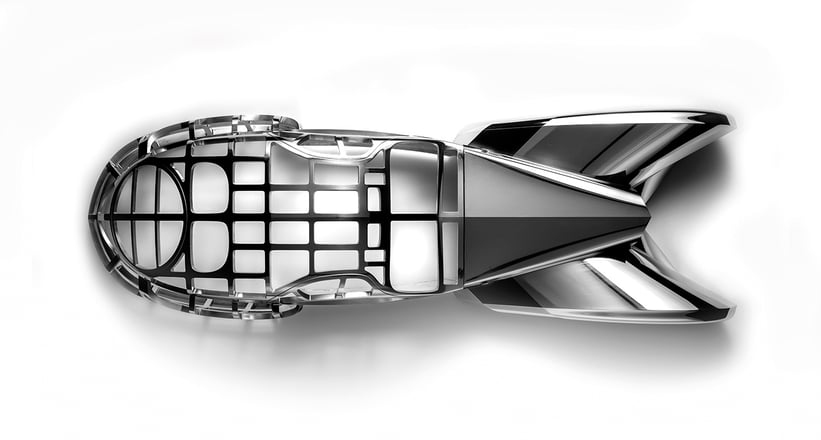

My latest sculptures draw their inspiration from the calligraphic sign ‘ENSO’, which means ‘circle’ in Japanese, and represents an expression of a moment — a moment when the mind is free to simply let the body create. The car used for the Chronosculpture here is a Porsche 964 RS, which provides an endless source of fascination. Power is nothing without control, and this sculpture embodies the acceleration of a car into a drift. This isn’t A to B travelling — it’s a driver on the edge of control.

How does it make you feel to be one of the few remaining Frenchmen at Bugatti?

I was born in Paris, so as a Frenchman, it’s an honour to represent my country at the very top of the automotive industry. Today, I’m the director of interior design and am also responsible for the design of our licensing products. Although my office is in Wolfsburg, I often get to travel to our HQ in Molsheim, and it always feels great, like a homecoming.

Does creating for yourself rather than for the manufacturer change the way you approach the process?

With design, you’re making products that attract a lot of people, customers, and future prospects. But you create art for yourself, regardless of whether anyone likes it or not. When you stand in front of the canvas or sit with an open sketchbook, you have the opportunity to express yourself and your innermost motivations. It opens the mind and one can learn a lot from the process.

How would you describe the relationship between art and cars – are the two distinguishable?

The ‘Orphism’ movement described speed using dynamic and rhythmic forms, but it was a small group of artists who shared a goal of moving beyond concrete reality to present a flowing vision of simultaneity and flux. Automotive exterior design is always a search for dynamic sculpture, even when stood still. More lately with the ‘Bauhaus’, with its rigour and Germanic look, artistic creativity and manufacturing were redefined. The revolution applied to car design — obvious on the first-generation Audi TT, for example. We can clearly see that art and cars have a strong relationship, and personally, I’m motivated to create aesthetically pleasing objects, down to the smallest details, like a great driving and pioneering car. At Bugatti specifically, it’s not so much about finding what’s next, but rather a love of beauty. To me, Bugattis are works of art. In the creative process, you’re forced to fight against time, as time is the enemy. But the Bugatti form has to last forever.

What can we expect from Etienne Salomé in the future?

My creative output, be it design or art, is something that comes from the heart. It’s not a rational process, but rather the result of love. Passion is what drives me, and my next works will represent this mind-set. The idea of someone saying, “It’s not so bad,” about my art freaks me out — I believe in a love or hate relationship!

Photos courtesy of Etienne Salomé © 2018