Two hundred and forty-eight miles per hour. That’s the extraordinary, bottom-clenching, cold sweat-inducing top speed the Sauber-Mercedes C9 of Mauro Baldi, Kenny Acheson and Gianfranco Brancatelli recorded on Les Hunaudiéres during qualifying for the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1989.

On race day, it was the sister Silver Arrow of Jochen Mass, Manuel Reuter and Stanley Dickens which clinched victory in the French endurance classic. There was no doubting it – for the first time since the mid 1950s, before it withdrew from international motorsport following the Le Mans tragedy of 1955, Mercedes-Benz was back on top of the motorsport world.

The 750HP, twin-turbo, V8-powered C9 sports-prototype was no less dominant in the World Sportscar Championship in 1989, of which Le Mans was unusually not a part that year. The Silver Arrows vanquished the opposition, scoring eight of a possible nine wins, losing out only at Dijon-Prenois where the blistering heat proved too much for the car’s Michelin tyres to bear. By no means was Mercedes’ path to Group C glory plain sailing, however.

Having provided a degree of support, including the provision of engines, to Sauber from 1985–1987, Mercedes committed to an all-out factory assault in 1988 with the comparatively tiny Zurich-based outfit, coinciding with the launch of its DTM programme with the 190E 2.3-16 saloon. Porsche, its next-door neighbour in Stuttgart who’d dominated the Group C formula with its formidable 956/962 prototype, had benefited enormously from endurance racing, both in terms of technological advancement and corporate image.

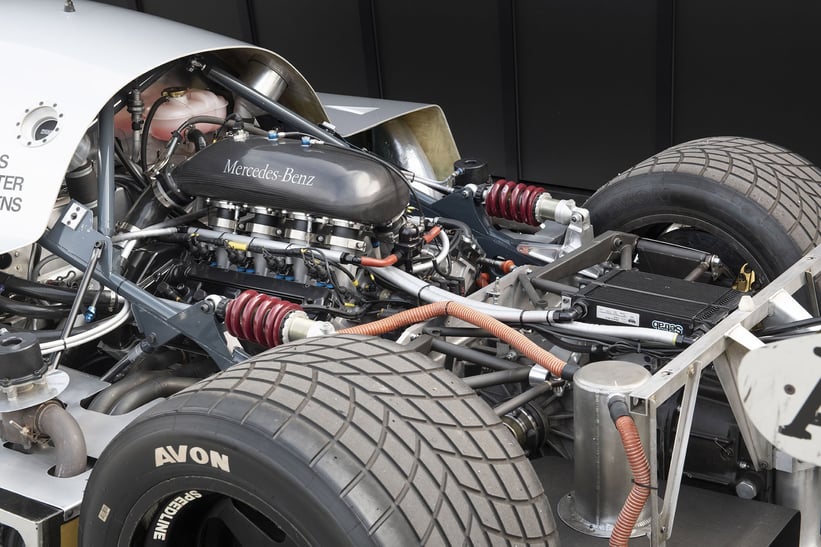

The Sauber-built C9 boasted an incredibly rigid aluminium monocoque chassis, longitudinal rear dampers to reduce the ride height, a wind-cheating silhouette body and the five-litre, twin-turbocharged Mercedes M118 and M119 production-based engines, built and tuned in Stuttgart. Said engines were the C9’s trump card – despite producing as much as 800HP in qualifying spec, they only revved to 7,000rpm, which reduced stress and thus increased efficiency, especially in slower speed corners, and reliability.

For 1988, Team Sauber Mercedes was sponsored by the Daimler-owned AEG-Olympia, resulting in a fantastic circuit board-inspired livery. The new Works team scored five victories that year, including the season-opener at Jerez, and despite having to withdraw from Le Mans because of a potentially lethal tyre issue, it proved that it was a force to be reckoned with. Finally, in 1989, with its cars painted bare silver to evoke the memory and success of its all-conquering Silver Arrows from the past, Mercedes swept to victory.

Ah, the halcyon days of Group C sports car racing. It was an epoch when plucky privateers stood every chance of knocking major manufacturers off their perches, grids and grandstands alike were bursting at the seams and the technological envelope was pushed so far that the sport’s free spirit actually had to be curtailed.

The tens of different wedge-shaped prototypes, more often than not adorned with household brand logos and driven by the world’s finest drivers, were, from a visual point of view at least, not especially delicate. But the way they manipulated the air with their concealed tunnels and dams to essentially glue themselves to the road at high speed was sheer sorcery. Pioneered by Lotus’ Colin Chapman in the 1970s, ‘ground effect’ was devastatingly effective and resulted in speeds that would simply never have been deemed possible a mere decade earlier.

The Mercedes-Sauber C9 truly harnessed the technology of the time. The example that’s currently offered for sale by Duncan Hamilton ROFGO, chassis 89-C9-A1, served as a spare car for the 1989 season and never turned a wheel in anger. It was then used as a display car the following year.

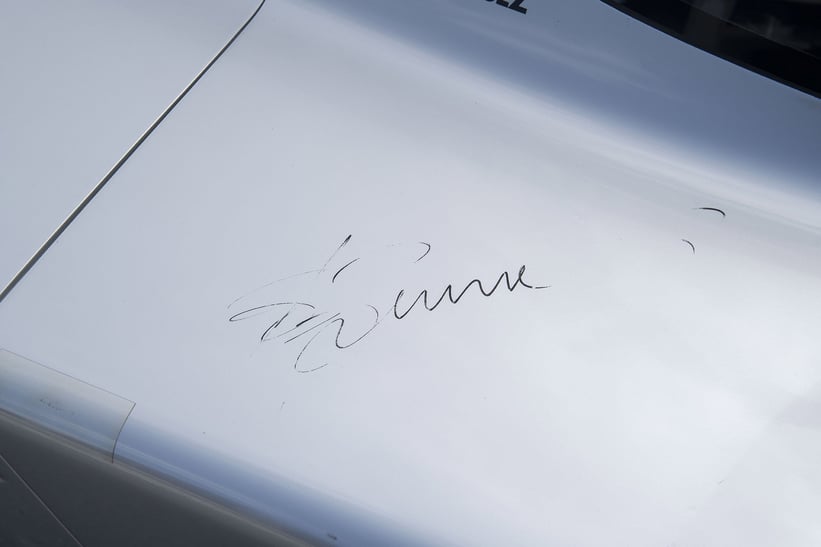

Interestingly, the majority of its silver body panels are believed to be those of the Mass/Reuter/Dickens C9 which won Le Mans in 1989. The beautifully preserved car wound up in the famous Donington Museum in the UK, until it was bought by a well-known Group C collector and racer in 2017 when the collection was dissolved.

BBM Sport in the UK, an outfit with a wealth of experience working on Sauber-Mercedes Group C prototypes, was commissioned with restoring 89-C9-A1 back to race-ready condition, the process of which included the fitment of reverse-engineered parts that were missing from the display car, including the bellhousing between the engine and the gearbox and the suspension rockers.

The turbocharged V8 engine and five-speed gearbox were also treated to full rebuilds and new internals by Xtec Engineering. Upon completion, an invitation to the 2019 Goodwood Festival of Speed promptly arrived in the owner’s inbox, which was duly accepted. Today, this magnificent Sauber-Mercedes is race-ready, and would no doubt make for a highly competitive entry into Peter Auto’s fiercely popular historic Group C series.

The Silver Arrows sports-prototypes of the 1980s and ’90s are among the greatest racing cars of all time and delivered on Mercedes’ promise to conquer the motorsport world, just as the marque had done in the 1930s and the 1950s. But furthermore, they also served as a springboard for Mercedes’ further expansion into the world of Formula 1, first via Sauber and McLaren and then with its own dedicated Works effort. And we all know how that’s turned out…

Photos courtesy of Duncan Hamilton ROFGO © 2020