The crazy characters of Zolder

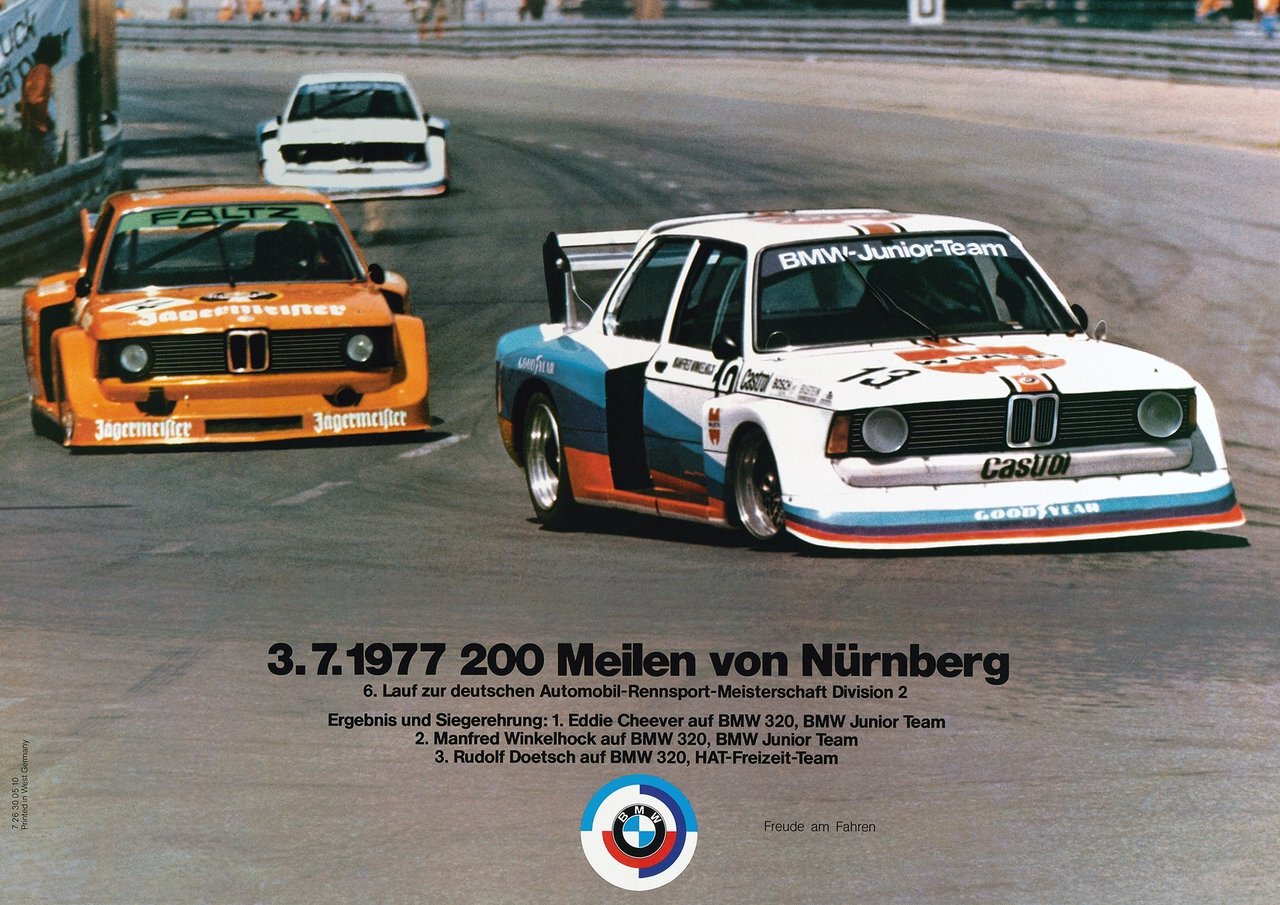

We would’ve loved to have overheard the comments in the grandstands when the chequered flag dropped at Zolder after the first round of the 1977 German Racing Championship. Something truly incredible had happened. BMW had entered three newcomers — Marc Surer, Manfred Winkelhock, and Eddie Cheever — whom no one had ever heard of and, to be honest, looked more like rock musicians than racing drivers. Driving the mighty Group 5 BMW 320s, the trio fought furiously to secure 1st, 3d, and 5th in class, respectively.

Even today, former team boss Jochen Neerpasch is not someone who smiles easily, but the wry grin on his face as he recalls the scenes in Belgium that year suggests he holds fond memories of the occasion. “We were prepared, but our competition didn’t know what to expect,” he remembers. “We wanted the Junior Team to drive disrespectfully — they weren’t disciplined. There was no strategy and certainly no team orders. That was the only way they could develop.” Sure enough, BMW’s three musketeers were all penalised in the following races for various reasons, but at the end of the first season, Cheever and Surer tied for 5th place, while Winkelhock finished an impressive 3rd overall.

What Neerpasch started would be unthinkable in today’s era of red tape and corporate group decision-making. As BMW Motorsport’s first managing director, he was able to quickly convince the top brass of the advantages of a professional organisation to promote young driving talent. The Junior Team’s creation, as he says, had personal roots. “As a driver, I suffered from migraines during weather changes. I visited a doctor and he told me that racing was not a sport, since the cars did all the work. I felt alone.”

The freedom to race

“They really were the good old times,” commented Marc Surer. “I’d love every driver to experience what we did — it was about being faster than your teammate, even if the cars touched. It was the sheer freedom to race.” Along with the Swiss, American Eddie Cheever was part of the original Junior Team. “Of course, I still live to beat Marc!” he jokes. “But in all seriousness, that was our first chance to prove ourselves as drivers. BMW provided the cars and Jochen Neerpasch was a serious and methodical teacher who taught us so much. We left our childhoods behind us.” Surer, Winkelhock, and Cheever built on these foundations and forged careers that lead to Formula 1.

For the Junior Team’s 40th anniversary, BMW invited the key players from that time to an informal reunion of the class of 1977, along with Jens Marquardt, the current director of BMW Motorsport and Jochen Neerpasch’s heir. The memory of Manfred Winkelhock, who was killed in a crash in Toronto in 1985, resonated throughout.

Much has changed in motorsport since the Junior Team’s casual and downright cheeky beginnings. Yet Marquardt retains Neerpasch’s principles. “Our current junior programme is very much in line with the original,” he explains. “We screen junior drivers from around the world, in feeder series such as Formula 3, to observe who shows a good and consistent performance.” Selected talents are then entered into a three-year training programme with an engineer. For Marquardt, character plays just as much of a role as physical fitness and technical knowledge.

Professional training

When Neerpasch launched the team of champions, the training was certainly not as sophisticated as it is today — even the use of social media is on the new curriculum. Surer and Cheever remember their working days beginning at 7:00am. “We were given a race car, equipment, and a coach who told us what to do,” recalls Surer. “Once the car was warm, we didn’t wait around to get out and practice. And above all, we felt equal to the older, more experienced pilots, such as Hans Stuck and Ronnie Peterson.”

As Surer explains, there’s one crucial difference in today’s training: “We never had an instructor teaching us how to drive. We were alone in the car, without telemetry.” As Sebastian Vettel and Timo Glock before him, Jesse Krohn, BMW Motorsport’s Junior of the Year in 2014, graduated from the racing school. “Today, all the data is captured, so if you make a mistake, the team knows about it straight away!” But the young racer believes this is actually an advantage. “Of course, there’s more pressure, but it’s good for future development because you’re better prepared.” Unlike his predecessors from 40 years ago, Krohn also works on the simulator, allowing him to practise on any track virtually before doing it in reality. “The tools have changed, but not the objective,” comments Cheever, citing new challenges the talents of today must face. “They’re closer to perfection than we were. Take recognising the braking points for example — we often just relied on pot luck.”

The route is the goal

Of course, BMW itself has had to adapt over the last four decades. “My job is to guarantee the vision of Jochen Neerpasch,” concludes Marquardt. “But we’re a global brand today, with markets in Hong Kong and Macau, for example.” He and his young pilots are currently adapting to the gradual electrification of motorsport. BMW’s participation in Formula E is a good example for him, especially as the i8 acts as a safety car for the series. “Old-school motorsport enthusiasts are sceptical because they can’t understand the great importance of social media in racing. But we have to do more to get young people excited about cars.” But for those who’ve been fans of the sport for decades — such as the father of the Junior Team — it’s difficult to excited about these new developments. “I still don’t understand Formula E as a racing sport; it’s rather as a preliminary experiment,” comments Neerpasch. “But it’s important that BMW is there, nonetheless, and that we continue to inspire the younger generation.”

One thing certainly hasn’t changed over the course of the last 40 years — the casual allure of those young and wild heroes from the original Junior Team. Jesse Krohn, who dreams of Le Mans and Daytona, truly loves his job. “I think drivers like Marc and Eddie are still heroes — and that these role models exist is a really good thing.”

Photos: BMW Archive