It was in 1959 that Richard Attwood made his competitive debut at Goodwood, encouraged by his father, who owned a chain of prosperous car dealerships in the Midlands and had previously dabbled in motorsport himself. During the course of the following decade and seven seasons of professional motorsport, Attwood ascended through the single seater ranks to race BRMs and Lotus’ in Formula 1, the undisputed highlight of which was finishing second to Graham Hill in the 1968 Monaco Grand Prix.

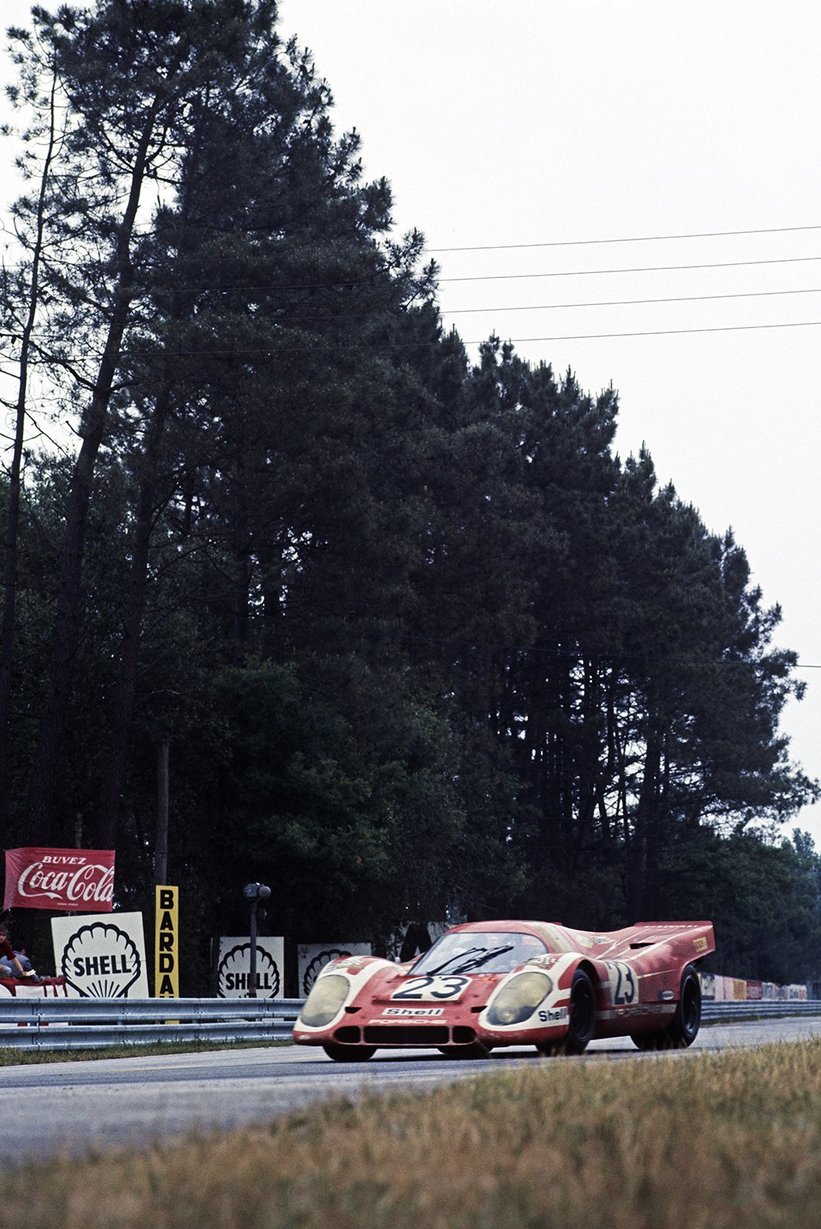

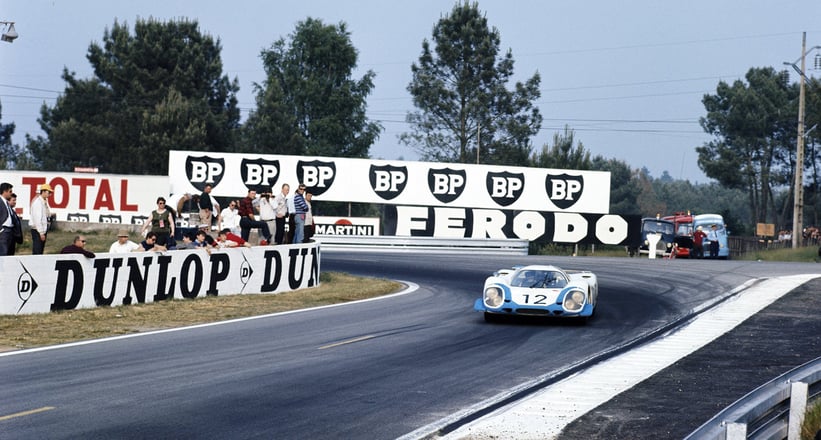

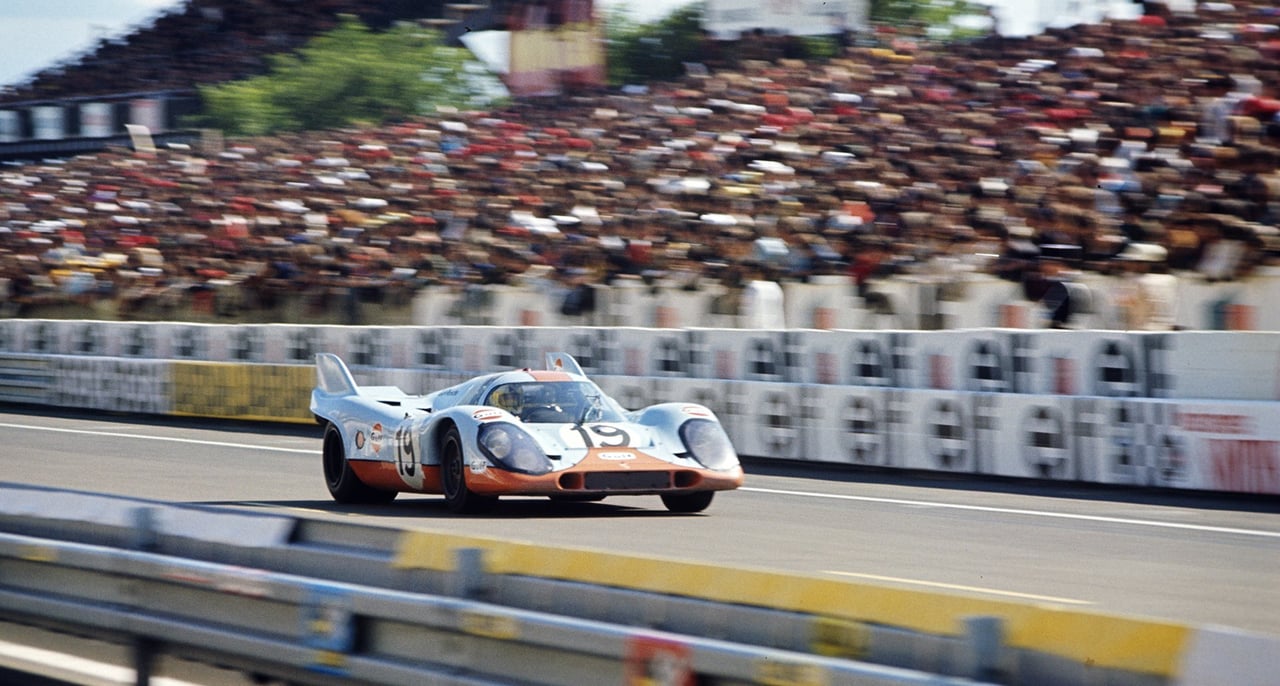

Attwood found his true calling, however, in sports-car racing, culminating in that momentous Le Mans win in 1970 together with Hans Herrmann, kindling Porsche’s formidable legacy at the French endurance classic. In this, the 50th anniversary of that victory and Attwood’s 80th year, we spoke with him about taming the Porsche 917, filming Le Mans with Steve McQueen and, of course, winning at the Circuit de la Sarthe.

Can you remember your first competitive race?

It was at Goodwood in 1958 driving a Standard 10, which was a saloon car around the same size as a Morris Minor. Before you could race at Goodwood you had to go down there and prove you could drive a car properly. I drove all the way from Wolverhampton, which in those pre-motorway days took around seven hours, and I passed the test. I entered my first race shortly afterwards and although I can’t remember where I finished or how competitive the car was, there’s a photo of me in Autosport magazine that proves I was there. To be honest, I was simply elated to have qualified to race in the first place!

How did racing sports cars compare to single seaters?

We didn’t really compare one form of racing to another and I didn’t necessarily choose single seaters or sports cars. We just did what we did and went from one step to another. You never knew where the next drive was coming from, and if the car was reasonably competitive and the offer was good, we were quite happy to race anything. There were no exclusivity contracts like there are today, which is probably difficult for people to understand.

How did you wind up driving for Porsche in 1969?

Huschke von Hanstein knew that Porsche was going to make a big push to win everything in 1969 and ’70 and was looking for drivers. Because Porsche wanted drivers of different nationalities to promote its cars around the world, I was teamed up with Tetsu Ikuzawa from Japan for a race at Watkins Glen in 1968. I got the factory drive the following year on the back of that.

Is it true that you very nearly signed for John Wyer to race the Ford GT40 instead?

Yes, at the back end of 1968, John Wyer asked me to drive for him. But once the negotiations with both sides were over, I had to face him and decline his offer. He was really upset, but overall, I saw better prospects with Porsche than Ford and its five-year-old GT40s. Porsche had actually said that it was going to bring new cars to each race, which didn’t happen in the end. But when we arrived at Daytona, sure enough there were five brand spanking new cars which had never even been tested. They were full of glass-fibre bits and we had to wear goggles because the shards were flying around the cockpit.

Just how different was the revised Porsche 917K than the original long-tail car?

The difference really was night and day. With regards to the original Porsche 917, you simply cannot believe how uncomfortable, unstable and dangerous a car can be. We were doing furious speeds, those which had never been seen at Le Mans before, and it was frightening. The driver had to be right on top of the car, because at any moment it could take its own course. It’s the only car I ever drove in which I had to lift for the kink on the Mulsanne straight. At Le Mans in 1969, we were leading by miles with three hours to go when the gearbox failed. I’d never won the race before and we had it on a plate, but I can honestly say that when the car broke, I was buzzing to get out. The short-tail 917 was perfect and, by comparison, a walk in the park!

It’s fair to say that come race day at Le Mans in 1970, the odds weren’t exactly in your favour…

The guys at Porsche knew that 1969 had been miserable, so in February of 1970 they called to ask what configuration of car I wanted to drive at Le Mans. I’d never been asked that by a manufacturer before. I told them I wanted a short-tail car and to be paired with Hans Herrmann, because he was the most experienced endurance driver.

Despite getting everything that I asked for, our car had the smaller 4.5-litre engine and during practice we were so slow, losing great amounts of time out of Mulsanne and Arnage corners especially. After qualifying, I actually remember saying we had no chance of winning. To add insult to injury, my glands were swollen on the day of the race and I couldn’t eat anything with any flavour. We didn’t have team doctors or physicians back then and I survived by drinking milk!

At which point did you realise the tables had turned in your favour?

Hans started the race and I had the pleasure of spectating. It was as frantic as a Grand Prix and I just couldn’t believe it – so many cars had a legitimate claim to the win, and I knew the race couldn’t go on like it had started. And, of course, it didn’t. All sorts of silly things happened: there was an accident involving three Ferraris, Jo Siffert over-revved his engine and Mike Hailwood failed to stop for wet tyres in good time.

I wasn’t interested about where we were because we were so outperformed. And then after 10 hours, someone told me we were in the lead. I was dumbfounded. The greatest difficulty was then defending that lead for 14 hours in the most difficult conditions. I can’t describe how wet it was and it felt like we were driving so slowly. There was a lot going on, but we ran a scheduled race, our pitstops were exactly as planned and I can’t remember any trouble at all.

What do you recall about the end of the race?

Hans wanted to finish the race and I couldn’t care less so long as he brought the car home safely, which I knew he would. We didn’t have a podium ceremony that year – we were instead taken around the circuit on the back of a lorry, which wasn’t particularly elegant. Porsche held a special dinner, but I was wiped out and couldn’t physically stay awake. It was embarrassing but I had to leave after 20 minutes. When I got back to England and saw my doctor on the Tuesday after the race, I found out I had mumps. To me, it was just another race, but Le Mans has become much bigger now.

What was it like to work with Steve McQueen on the production of Le Mans?

I was in the 917 camera car for virtually the entire film. The filming was very slow and there was always someone sticking their oar in saying the light wasn’t right or something else. There was so much time wasted, and you can see why it cost so much – if I worked just a few days a week I earned more money than I did racing! There was a lot of euphoria when filming started, and many high-profile drivers signed up. But a lot of them drifted away because it wasn’t exciting enough for them. But McQueen was a great enthusiast and a very talented guy. He was in awe of us and we were in awe of him. He was absolutely crestfallen when the insurance company banned him from driving during filming.

Did you realise at the time that you were racing in what is now considered to be the golden era of endurance racing?

It was a very nostalgic era and I think the film shows that. Sure, you never know what the future holds, but the cars were charismatic and the camaraderie was a major part of what it was all about. Today’s racing drivers’ lives aren’t threatened like they used to be, which I think made the sense of community greater in my day. Once Colin Chapman discovered downforce, racing lost a lot of its attraction for me. That’s why so many people go to Goodwood to see cars moving around on their own – it’s pure artistry. They call it progress, but sometimes progress means regress.

You famously bought a Porsche 917 as your ‘pension’ – do you regret selling it?

Yes, I bought a Porsche 917 from Brian Redman in 1978. Neither of us knew about its history but we eventually discovered it was the Solar Productions camera car from the film Le Mans, which I’d driven more than anybody else! I don’t regret parting with it because I needed the money. It was a case of selling the car or the house, and I like my house too much.

Photos courtesy of the Porsche Museum © 2020