After Automobili Lamborghini's creative ‘self-discovery phase’ with the 350 and 400 GT models between 1963 and 1966, the birth of the Miura had a decidedly shocking effect on the sports-car scene around the world. This bullish-looking automobile was the first clear warning shot across the bows of celebrated rival Ferrari in Maranello. Ferruccio Lamborghini had found suitable engineers to implement his product philosophy: Paolo Stanzani and Gianpaolo Dallara. Fresh from university, the two ‘young rebels’ immediately managed not only to challenge the already established designer and entrepreneur Enzo Ferrari, but also to overcome his genius. Compared to the Miura, the Ferrari Daytona simply seemed too conventional. Undoubtedly, it was a beautiful and technically advanced car, but it lacked the last touch of inspiration that set the provocative Miura apart.

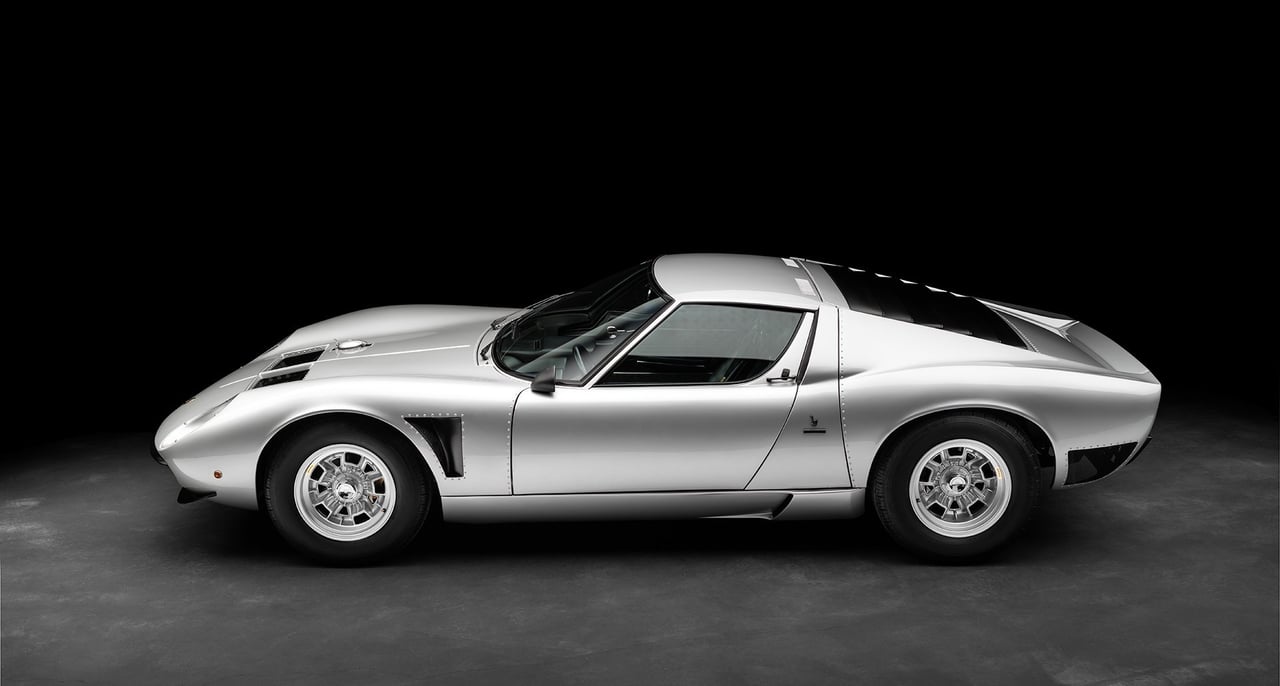

The key innovation of the Miura was installing the 12-cylinder engine in the centre, but transversely to the direction of travel. This allowed for the perfect weight distribution and wheelbase dimensions, while keeping the proportions as compact as possible. According to Stanzani: “To be honest, we were inspired by the pioneering idea of the Mini’s chief engineer. However, in the Mini, the gearbox was placed under the engine. In this configuration, the Miura's centre of gravity would have been too high. So we just placed it next to the engine”. Young designer Marcello Gandini, delighted by the ideal proportional requirements, transformed that technical ‘stroke of genius’ into one of the most stylistically beautiful sports cars of all time.

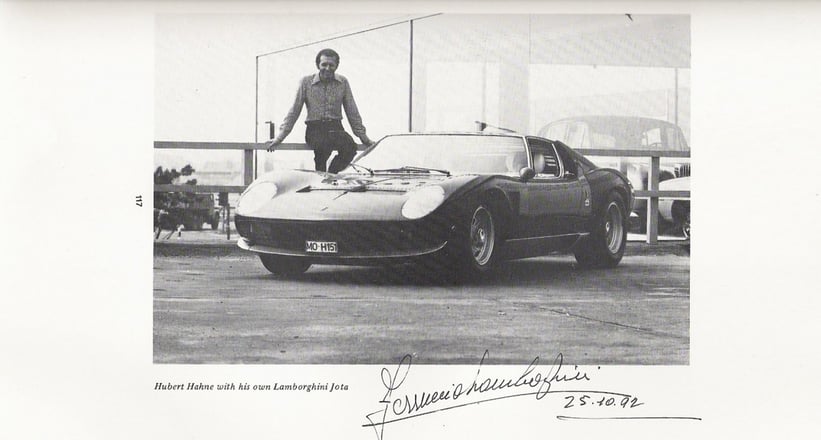

The culmination of the Miura era is embodied by the very last variant of the car, one of which was built for my father, Hubert Hahne. His Lamborghini Miura SV ‘Jota’ – later commonly called SVJ – with chassis 4860 was the fourth and last SVJ officially built in period by the Sant'Agata factory, before the Miura production came to an end in October 1973.

One of the most spectacular cars in Lamborghini’s history was conceived over a glass of wine, during a meeting between my father and Ferruccio Lamborghini at his estate in the summer of 1972. Hubert, besides being the German Lamborghini importer and a successful racing driver, was a great friend of Ferruccio. Later on that day, while smoking his cigarette and looking at him, Ferruccio said: “We have already modified three SVs into these special SVJs. Why can’t we modify a last one for a dear friend of the brand like you? If we earn money and you are happy, let’s do it! Let Ubaldo (Sgarzi) know what you want”. At that point, the green light was given to start Hahne's special car, which had been annotated in the factory’s commercial register as ‘Jota’.

My father wanted to have the car in black with a matching black interior. He considered it to be a final tribute to the Miura that was so close to his heart – and that was about to leave the sports-car scene, to be replaced by the breathtaking Countach. He often said: “For me, the end of the Miura is like a funeral. The all black ‘Jota’ is my way of paying homage.” I remember my father telling me that he personally supervised the build of his very special car in November and December 1972 at the factory in Sant’Agata. When the craftsmen at Reparto Assistenza Clienti were removing the rear hexagonal grille (as was done on the three previous SVJs), my father raised an eyebrow and asked: "But why do you want to remove one of the most distinctive and elegant details of the Miura? Looking at those blue springs and suspension arms from the back is not a flattering view of the Miura’. Then, he gave his instructions: “Cut the grille only where the quad pipes of the open exhaust come out – and please add more rivets. The car must look menacing from standstill and I don’t want it to look like the other three.”

But Hubert wasn’t done yet: he had even more very specific requests: “Please leave two wipers. When I drive fast in the rain, I need security.” Or: “Please don’t install the passenger-side mirror. As I mostly overtake or stay on the left lane on the Autobahn, I don’t need that accessory that ruins the line of the car.” Or: “Install the strongest Bosch headlights available, instead of Carello ones, as the car must be compliant with the German regulations and I need visibility in the night!” Last but not least: “Install stiffer suspension and replace the spinners with Borrani central nuts.” My father was definitely a gentleman with an appreciation for details! Needless to say his particular wishes were fulfilled and the car was built with the utmost care by a team of devoted craftsmen using the best components and materials. The result was a winning combination of Italian craftsmanship and German accuracy. After much debate, Ferruccio finally convinced my father to refrain from the mournful monochrome combination he wanted and the ‘Jota’ was finally delivered to him on 30 April 1973 with a black and white interior.

Behind the factory walls, the car was soon known as ‘La Jota di Hahne’ – Hahne’s Jota. And of course, the new owner did not miss the opportunity to pick the car up from its birthplace. The fact that the ‘Cavaliere del Lavoro’ – Ferruccio Lamborghini himself – had fine-tuned the finishing touches was by no means obvious. But being a perfectionist, he was bothered by some small dirt spots on the glossy and delicate black paint. I remember my father commenting on the fingerprints left on the paintwork by passing people when the car was parked, as well as the difficulties of cleaning it after his ‘spirited’ drives to the countryside or on the Autobahn, often resulting in a “cemetery of crashed insects and flies” on the bonnet and windshield.

Since the specially split sump tuned engine had already completed its run-in phase on the dyno at ‘Sala Prova Motori’, my father was able to immediately savour the V12’s overwhelming 400-plus horsepower. To achieve this output, high-compression pistons were fitted, as well as specific sport camshafts. Those were combined with perfectly tuned carburettors and the open exhaust. Hubert wanted the high-rev power to go fast on the Autobahn, so a specific oil cooler was installed under the front radiator. To increase the safety of passengers at these speeds, special four-point Britax safety belts were fitted. And for greater control at high speeds, the SVJ received a small-diameter steering wheel – just like in my father’s racecars.

With the delivery paperwork signed and a fresh factory guarantee in his hands, Hubert himself drove the car from Sant'Agata to Düsseldorf. Especially on the Autobahn, it must have been an incredible sight for drivers to be overtaken by such a mighty machine! At close to 300kph, the open exhaust must have sounded like a fighter jet during take-off.

But the ‘maiden voyage’ of the Jota did not go unnoticed by the authorities. Between Frankfurt and Cologne, there was a roadblock. Every car was checked and only my father was stopped. Surrounded by many police officers, the chief commissioner accused him of having passed somewhere in Bavaria, driving way too fast. They had tried to stop him for hundreds of kilometres without success. Another officer, flabbergasted by the sight of the Heuer Rally Master stopwatches positioned in front of the gearlever, still running, even asked: “Are you competing in a race, Herr Hahne? You should really slow down with this Rakete or you will get into serious trouble.” My father replied, almost sincerely and innocently: “I always kept to the speed limit, Herr Polizist, but thank you for the advice.” Shortly afterwards, there was a conference call with various police stations and even a helicopter pilot. Eventually, it was concluded that he could not be proven guilty. And being a famous racing driver in Germany certainly helped his cause!

After this almost trouble-free first run from Italy to the Hubert Hahne Automobil-Vertrieb GmbH headquarters in Düsseldorf, the ‘Jota’ was homologated in Germany and the second identification plate – typical of each Lamborghini delivered there – was riveted to the chassis. In the Fahrzeugbrief (the title), the car was registered in Hubert’s name in his hometown of Moers and described as a ‘Lamborghini P400 Miura SV Jota 4860’ – my father wanted his car to be homologated as a specific model, not just as a standard SV. The SVJ was never officially offered for sale and therefore was not a model homologated by the factory. In fact, the special factory ‘Jota’ badge – added to the rear panel and unique to 4860 – was also meant to let other Miura owners know why they had just been overtaken.

According to my father’s brief to Ferruccio Lamborghini and Ubaldo Sgarzi, the ‘Hahne Jota’ was specially developed to reach 300kph and cover over 500km on a single tank of fuel. The team at ‘Reparto Assistenza Clienti’ came up with the ingenious solution of removing the spare wheel and mounting a specially built 110-litre fuel tank with an external quick filler, which increased not only the car’s range, but also its front downforce, as the Miura had tended to be too light at high speeds. It was another feature unique to chassis 4860.

My father commented on the result of Ferruccio's work as follows: “Although I was able to let off steam on the racetracks at that time, I took every opportunity to make long journeys with the ‘Jota’. With my contribution and thanks to my expertise as a racing driver, Lamborghini did a great job with this car. It was perfectly tuned.” Obviously, there was no built-in radio – the musicality of the 12-cylinder engine and the experience of exerting its almost inexhaustible power was the best entertainment programme one could wish for. The ‘breakfast journey’ from Düsseldorf to Paris took only two and a half hours and Hubert always kept a close eye on the Heuer Rally Master double stopwatches. Sunday mornings started at 6.00am, with an arrival time at Rue de Grenelle of 8.30am. “It was like traveling on a sports airplane”.

Three other examples of the so-called SVJ were produced for Lamborghini’s VIP customers, all painted in almost the same hue, but according to my father and others, there were only two ‘real Jotas’ built at Sant'Agata: the Bob Wallace original that sadly was lost – and his own car, which was directly inspired by the former. It was beautiful, powerful, unique thanks to its many details, and a true embodiment of my father’s ‘racing soul’.

In 1976, Hubert had the ‘Jota’ repainted at the factory in silver and fitted with a black leather interior. Over time, this became the car’s most famous livery and it has remained so ever since. Silver hinted at the colour of my father’s racing cars as well as being a tribute to the traditional colour of German motorsport. The silver livery was completed by another interesting detail requested by my father: He had all the glass frames and other chrome parts repainted in matte black. His idea was to avoid reflections from the sun when he was driving fast – and certainly to give the car an increased ‘racing appeal’.

After 28 years spent in Germany in the hands of my father and a few other passionate custodians, 4860 was considered missing. I do remember many collectors asking my father the whereabouts of his 'Jota'. In fact, a Japanese collector had purchased it in 2001, then a second one in 2004, and it only made some rare appearances in a few Japanese magazines and as die-cast scale model. In 2018, a collector and great enthusiast of the brand managed to purchase the car. He brought it back to Europe and subsequently to the Sant’Agata factory for a conservative restoration, carried out by the skilled people at Top Motors and Cremonini who had helped to write the global success story of the Miura. The conservative restoration, aimed at keeping the car as original as possible, was done under the auspices of the Lamborghini factory and its Polo Storico department, which undertook an exhaustive research and certification process. This led to the coveted Certificate of Historical Authenticity, which has been granted only to 4860 and one other SVJ so far.

As if by fate, my first contact with my father's ‘Jota’ after so many years was in one of his favourite cities – Paris! When I heard from enthusiasts and journalists that the ‘Hahne Jota’ would be exhibited at the Rétromobile show in Paris in February 2020 at the Lamborghini stand, I left immediately, covering 2,500km in two days. I convinced my girlfriend by saying: “Would you like to have breakfast in Paris?” Luckily she likes macarons, so she accepted.

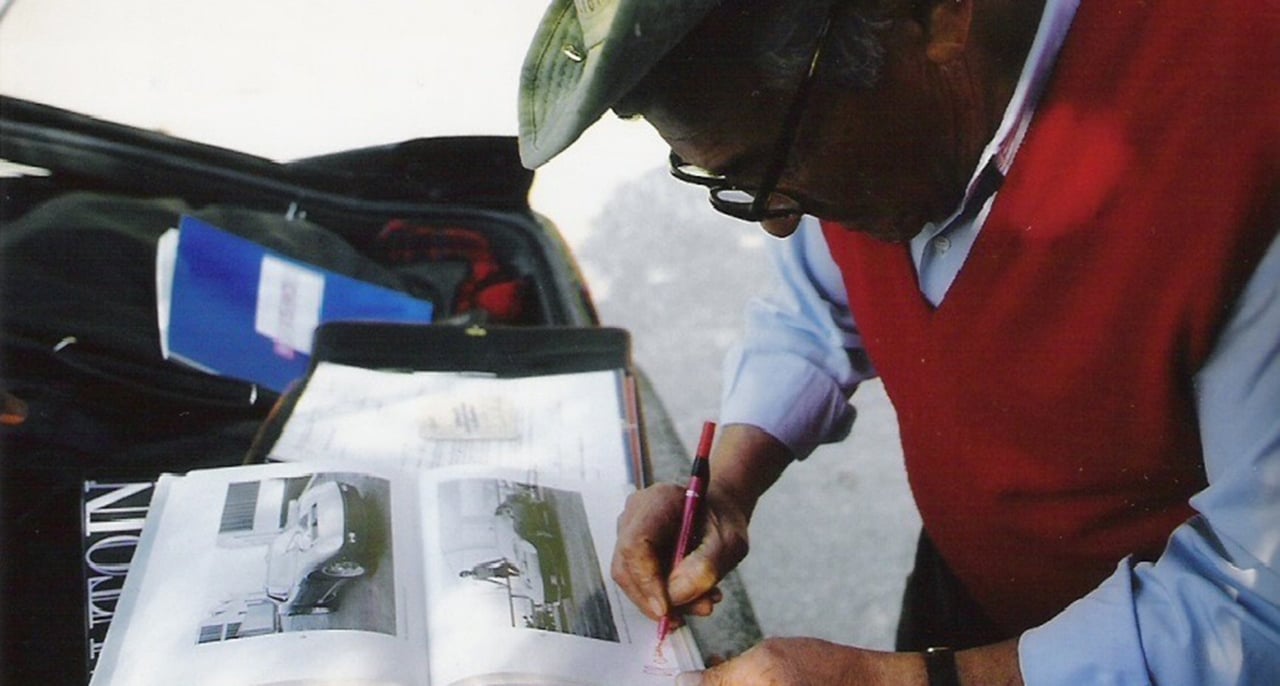

As soon as I saw the car again in the metal, childhood memories immediately came to mind and I suddenly became very emotional. I remembered the last meeting with Ferruccio in 1992 when we were guests at his ‘La Fiorita’ estate. After signing one of my father's numerous Lamborghini books, in which he was pictured next to his ‘Jota’, Ferruccio put a glass of water on the hood above the V12 of the Mercedes S-Class my father owned at that time to test the motor vibrations – just like he had checked the airbox of his red Miura SV with his famous ‘cigarette test’. My father also kept up a great friendship with the technical founding father of the Miura, Paolo Stanzani, over the years. They often met to collaborate on various motor projects, such as the Countach Evoluzione and the Bugatti EB110.

Recently, I had the opportunity to drive my father’s incredible ‘Jota’ during a photoshoot at a racetrack in Italy, alongside legendary Lamborghini test driver Valentino Balboni. I felt what my father must have felt when he drove it for the very first time, leaving Sant’Agata. Hearing that exhaust note and feeling all that power wanting to be unleashed 10 centimetres behind my head really gave me goosebumps.

Still today, the ‘Hahne Jota’ perpetuates the spirit of Bob Wallace's legendary racecar of dreams. And I’m certain that Ferruccio took pride in the fact that a conversation with a friend, while enjoying a glass of wine, led to the creation of one of the most important and famous ‘Raging Bulls’ – and certainly the fastest-driven Miura of all time!

Words by David Hahne

Photography by Pietro Bianchi, Alex Penfold, Alex Babington, Automobili Lamborghini SpA and the Hahne family